Iterating tables in batches

Rails provides a method called in_batches that can be used to iterate over

rows in batches. For example:

User.in_batches(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

endUnfortunately, this method is implemented in a way that is not very efficient, both query and memory usage wise.

To work around this you can include the EachBatch module into your models,

then use the each_batch class method. For example:

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

endThis produces queries such as:

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)The API of this method is similar to in_batches, though it doesn't support

all of the arguments that in_batches supports. You should always use

each_batch unless you have a specific need for in_batches.

Iterating over non-unique columns

You should not use the each_batch method with a non-unique column (in the context of the relation) as it

may result in an infinite loop.

Additionally, the inconsistent batch sizes cause performance issues when you

iterate over non-unique columns. Even when you apply a max batch size

when iterating over an attribute, there's no guarantee that the resulting

batches don't surpass it. The following snippet demonstrates this situation

when you attempt to select

Ci::Build entries for users with id between 1 and 10,000, the database returns

1 215 178 matching rows.

[ gstg ] production> Ci::Build.where(user_id: (1..10_000)).size

=> 1215178This happens because the built relation is translated into the following query:

[ gstg ] production> puts Ci::Build.where(user_id: (1..10_000)).to_sql

SELECT "ci_builds".* FROM "ci_builds" WHERE "ci_builds"."type" = 'Ci::Build' AND "ci_builds"."user_id" BETWEEN 1 AND 10000

=> nilAnd queries which filter non-unique column by range WHERE "ci_builds"."user_id" BETWEEN ? AND ?,

even though the range size is limited to a certain threshold (10,000 in the previous example) this

threshold does not translate to the size of the returned dataset. That happens because when taking

n possible values of attributes, one can't tell for sure that the number of records that contains

them is less than n.

Loose-index scan with distinct_each_batch

When iterating over a non-unique column is necessary, use the distinct_each_batch helper

method. The helper uses the loose-index scan technique

(skip-index scan) to skip duplicated values within a database index.

Example: iterating over distinct author_id in the Issue model

Issue.distinct_each_batch(column: :author_id, of: 1000) do |relation|

users = User.where(id: relation.select(:author_id)).to_a

endThe technique provides stable performance between the batches regardless of the data distribution.

The relation object returns an ActiveRecord scope where only the given column is available.

Other columns are not loaded.

The underlying database queries use recursive CTEs, which adds extra overhead. We therefore advise to use

smaller batch sizes than those used for a standard each_batch iteration.

Column definition

EachBatch uses the primary key of the model by default for the iteration. This works most of the

cases, however in some cases, you might want to use a different column for the iteration.

Project.distinct.each_batch(column: :creator_id, of: 10) do |relation|

puts User.where(id: relation.select(:creator_id)).map(&:id)

endThe query above iterates over the project creators and prints them out without duplications.

NOTE:

In case the column is not unique (no unique index definition), calling the distinct method on

the relation is necessary. Using not unique column without distinct may result in each_batch

falling into an endless loop as described in following

issue.

EachBatch in data migrations

When dealing with data migrations the preferred way to iterate over a large volume of data is using

EachBatch.

A special case of data migration is a batched background migration

where the actual data modification is executed in a background job. The migration code that

determines the data ranges (slices) and schedules the background jobs uses each_batch.

Efficient usage of each_batch

EachBatch helps to iterate over large tables. It's important to highlight that EachBatch

does not magically solve all iteration-related performance problems, and it might not help at

all in some scenarios. From the database point of view, correctly configured database indexes are

also necessary to make EachBatch perform well.

Example 1: Simple iteration

Let's consider that we want to iterate over the users table and print the User records to the

standard output. The users table contains millions of records, thus running one query to fetch

the users likely times out.

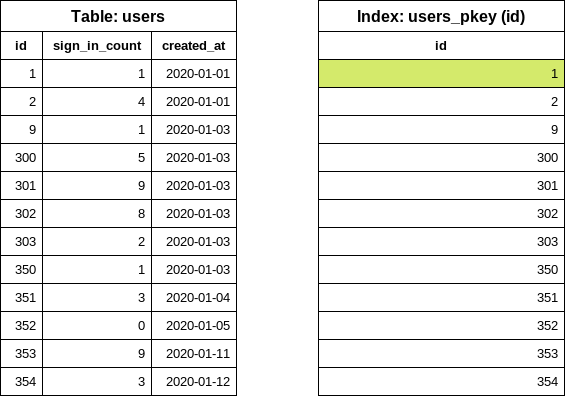

This table is a simplified version of the users table which contains several rows. We have a few

smaller gaps in the id column to make the example a bit more realistic (a few records were

already deleted). One index exists on the id field:

ID |

sign_in_count |

created_at |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2020-01-01 |

| 2 | 4 | 2020-01-01 |

| 9 | 1 | 2020-01-03 |

| 300 | 5 | 2020-01-03 |

| 301 | 9 | 2020-01-03 |

| 302 | 8 | 2020-01-03 |

| 303 | 2 | 2020-01-03 |

| 350 | 1 | 2020-01-03 |

| 351 | 3 | 2020-01-04 |

| 352 | 0 | 2020-01-05 |

| 353 | 9 | 2020-01-11 |

| 354 | 3 | 2020-01-12 |

Loading all users into memory (avoid):

users = User.all

users.each { |user| puts user.inspect }Use each_batch:

# Note: for this example I picked 5 as the batch size, the default is 1_000

User.each_batch(of: 5) do |relation|

relation.each { |user| puts user.inspect }

end

How each_batch works

As the first step, it finds the lowest id (start id) in the table by executing the following

database query:

SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1Notice that the query only reads data from the index (INDEX ONLY SCAN), the table is not

accessed. Database indexes are sorted so taking out the first item is a very cheap operation.

The next step is to find the next id (end id) which should respect the batch size

configuration. In this example we used a batch size of 5. EachBatch uses the OFFSET clause

to get a "shifted" id value.

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

end

```0

Again, the query only looks into the index. The `OFFSET 5` takes out the sixth `id` value: this

query reads a maximum of six items from the index regardless of the table size or the iteration

count.

At this point, we know the `id` range for the first batch. Now it's time to construct the query

for the `relation` block.

```ruby

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

end

```1

Notice the `<` sign. Previously six items were read from the index and in this query, the last

value is "excluded". The query looks at the index to get the location of the five `user`

rows on the disk and read the rows from the table. The returned array is processed in Ruby.

The first iteration is done. For the next iteration, the last `id` value is reused from the

previous iteration to find out the next end `id` value.

```ruby

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

end

```2

Now we can easily construct the `users` query for the second iteration.

```ruby

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

end

```3

### Example 2: Iteration with filters

Building on top of the previous example, we want to print users with zero sign-in count. We keep

track of the number of sign-ins in the `sign_in_count` column so we write the following code:

```ruby

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

end

```4

`each_batch` produces the following SQL query for the start `id` value:

```ruby

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

end

```5

Selecting only the `id` column and ordering by `id` forces the database to use the

index on the `id` (primary key index) column however, we also have an extra condition on the

`sign_in_count` column. The column is not part of the index, so the database needs to look into

the actual table to find the first matching row.

NOTE:

The number of scanned rows depends on the data distribution in the table.

- Best case scenario: the first user was never logged in. The database reads only one row.

- Worst case scenario: all users were logged in at least once. The database reads all rows.

In this particular example, the database had to read 10 rows (regardless of our batch size setting)

to determine the first `id` value. In a "real-world" application it's hard to predict whether the

filtering causes problems or not. In the case of GitLab, verifying the data on a

production replica is a good start, but keep in mind that data distribution on GitLab.com can be

different from self-managed instances.

#### Improve filtering with `each_batch`

##### Specialized conditional index

```ruby

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

end

```6

This is how our table and the newly created index looks like:

This index definition covers the conditions on the `id` and `sign_in_count` columns thus makes the

`each_batch` queries very effective (similar to the simple iteration example).

It's rare when a user was never signed in so we a anticipate small index size. Including only the

`id` in the index definition also helps to keep the index size small.

##### Index on columns

Later on, we might want to iterate over the table filtering for different `sign_in_count` values, in

those cases we cannot use the previously suggested conditional index because the `WHERE` condition

does not match with our new filter (`sign_in_count > 10`).

To address this problem, we have two options:

- Create another, conditional index to cover the new query.

- Replace the index with a more generalized configuration.

NOTE:

Having multiple indexes on the same table and on the same columns could be a performance bottleneck

when writing data.

Let's consider the following index (avoid):

```ruby

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

end

```7

The index definition starts with the `id` column which makes the index very inefficient from data

selectivity point of view.

```ruby

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

end

```8

Executing the query above results in an `INDEX ONLY SCAN`. However, the query still needs to

iterate over an unknown number of entries in the index, and then find the first item where the

`sign_in_count` is `0`.

We can improve the query significantly by swapping the columns in the index definition (prefer).

```ruby

class User < ActiveRecord::Base

include EachBatch

end

User.each_batch(of: 10) do |relation|

relation.update_all(updated_at: Time.now)

end

```9

The following index definition does not work well with `each_batch` (avoid).

```plaintext

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)

```0

Since `each_batch` builds range queries based on the `id` column, this index cannot be used

efficiently. The DB reads the rows from the table or uses a bitmap search where the primary

key index is also read.

##### "Slow" iteration

Slow iteration means that we use a good index configuration to iterate over the table and

apply filtering on the yielded relation.

```plaintext

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)

```1

The iteration uses the primary key index (on the `id` column) which makes it safe from statement

timeouts. The filter (`sign_in_count: 0`) is applied on the `relation` where the `id` is already

constrained (range). The number of rows is limited.

Slow iteration generally takes more time to finish. The iteration count is higher and

one iteration could yield fewer records than the batch size. Iterations may even yield

0 records. This is not an optimal solution; however, in some cases (especially when

dealing with large tables) this is the only viable option.

### Using Subqueries

Using subqueries in your `each_batch` query does not work well in most cases. Consider the following example:

```plaintext

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)

```2

The iteration uses the `id` column of the `projects` table. The batching does not affect the

subquery. This means for each iteration, the subquery is executed by the database. This adds a

constant "load" on the query which often ends up in statement timeouts. We have an unknown number

of [confidential issues](../../user/project/issues/confidential_issues.md), the execution time

and the accessed database rows depend on the data distribution in the `issues` table.

NOTE:

Using subqueries works only when the subquery returns a small number of rows.

#### Improving Subqueries

When dealing with subqueries, a slow iteration approach could work: the filter on `creator_id`

can be part of the generated `relation` object.

```plaintext

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)

```3

If the query on the `issues` table itself is not performant enough, a nested loop could be

constructed. Try to avoid it when possible.

```plaintext

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)

```4

If we know that the `issues` table has many more rows than `projects`, it would make sense to flip

the queries, where the `issues` table is batched first.

### Using `JOIN` and `EXISTS`

When to use `JOINS`:

- When there's a 1:1 or 1:N relationship between the tables where we know that the joined record

(almost) always exists. This works well for "extension-like" tables:

- `projects` - `project_settings`

- `users` - `user_details`

- `users` - `user_statuses`

- `LEFT JOIN` works well in this case. Conditions on the joined table need to go to the yielded

relation so the iteration is not affected by the data distribution in the joined table.

Example:

```plaintext

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)

```5

`EXISTS` queries should be added only to the inner `relation` of the `each_batch` query:

```plaintext

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)

```6

### Complex queries on the relation object

When the `relation` object has several extra conditions, the execution plans might become

"unstable".

Example:

```plaintext

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)

```7

Here, we expect that the `relation` query reads the `BATCH_SIZE` of user records and then

filters down the results according to the provided queries. The planner might decide that

using a bitmap index lookup with the index on the `confidential` column is a better way to

execute the query. This can cause an unexpectedly high amount of rows to be read and the

query could time out.

Problem: we know for sure that the relation is returning maximum `BATCH_SIZE` of records

however, the planner does not know this.

Common table expression (CTE) trick to force the range query to execute first:

```plaintext

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)

```8

### Counting records

For tables with a large amount of data, counting records through queries can result

in timeouts. The `EachBatch` module provides an alternative way to iteratively count

records. The downside of using `each_batch` is the extra count query which is executed

on the yielded relation object.

The `each_batch_count` method is a more efficient approach that eliminates the need

for the extra count query. By invoking this method, the iteration process can be

paused and resumed as needed. This feature is particularly useful in situations

where error budget violations are triggered after five minutes, such as when performing

counting operations within Sidekiq workers.

To illustrate, counting records using `EachBatch` involves invoking an additional

count query as follows:

```plaintext

User Load (0.7ms) SELECT "users"."id" FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) ORDER BY "users"."id" ASC LIMIT 1 OFFSET 1000

(0.7ms) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM "users" WHERE ("users"."id" >= 41654) AND ("users"."id" < 42687)

```9

On the other hand, the `each_batch_count` method enables the counting process to be

performed more efficiently (counting is part of the iteration query) without invoking

an extra count query:

```ruby

[ gstg ] production> Ci::Build.where(user_id: (1..10_000)).size

=> 1215178

```0

Furthermore, the `each_batch_count` method allows the counting process to be paused

and resumed at any point. This capability is demonstrated in the following code snippet:

```ruby

[ gstg ] production> Ci::Build.where(user_id: (1..10_000)).size

=> 1215178

```1

### `EachBatch` vs `BatchCount`

When adding new counters for Service Ping, the preferred way to count records is using the

`Gitlab::Database::BatchCount` class. The iteration logic implemented in `BatchCount`

has similar performance characteristics like `EachBatch`. Most of the tips and suggestions

for improving `BatchCount` mentioned above applies to `BatchCount` as well.

## Iterate with keyset pagination

There are a few special cases where iterating with `EachBatch` does not work. `EachBatch`

requires one distinct column (usually the primary key), which makes the iteration impossible

for timestamp columns and tables with composite primary keys.

Where `EachBatch` does not work, you can use

[keyset pagination](pagination_guidelines.md#keyset-pagination) to iterate over the

table or a range of rows. The scaling and performance characteristics are very similar to

`EachBatch`.

Examples:

- Iterate over the table in a specific order (timestamp columns) in combination with a tie-breaker

if column user to sort by does not contain unique values.

- Iterate over the table with composite primary keys.

### Iterate over the issues in a project by creation date

You can use keyset pagination to iterate over any database column in a specific order (for example,

`created_at DESC`). To ensure consistent order of the returned records with the same values for

`created_at`, use a tie-breaker column with unique values (for example, `id`).

Assume you have the following index in the `issues` table:

```ruby

[ gstg ] production> Ci::Build.where(user_id: (1..10_000)).size

=> 1215178

```2

### Fetching records for further processing

The following snippet iterates over issue records within the project using the specified order

(`created_at, id`).

```ruby

[ gstg ] production> Ci::Build.where(user_id: (1..10_000)).size

=> 1215178

```3

You can add extra filters to the query. This example only lists the issue IDs created in the last

30 days:

```ruby

[ gstg ] production> Ci::Build.where(user_id: (1..10_000)).size

=> 1215178

```4

### Updating records in the batch

For complex `ActiveRecord` queries, the `.update_all` method does not work well, because it

generates an incorrect `UPDATE` statement.

You can use raw SQL for updating records in batches:

```ruby

[ gstg ] production> Ci::Build.where(user_id: (1..10_000)).size

=> 1215178

```5

NOTE:

To keep the iteration stable and predictable, avoid updating the columns in the `ORDER BY` clause.

### Iterate over the `merge_request_diff_commits` table

The `merge_request_diff_commits` table uses a composite primary key (`merge_request_diff_id, relative_order`),

which makes `EachBatch` impossible to use efficiently.

To paginate over the `merge_request_diff_commits` table, you can use the following snippet:

```ruby

[ gstg ] production> Ci::Build.where(user_id: (1..10_000)).size

=> 1215178

```6

### Order object configuration

Keyset pagination works well with simple `ActiveRecord` `order` scopes

([first example](#iterate-over-the-issues-in-a-project-by-creation-date)).

However, in special cases, you need to describe the columns in the `ORDER BY` clause (second example)

for the underlying keyset pagination library. When the `ORDER BY` configuration cannot be

automatically determined by the keyset pagination library, an error is raised.

The code comments of the

[`Gitlab::Pagination::Keyset::Order`](https://gitlab.com/gitlab-org/gitlab/-/blob/master/lib/gitlab/pagination/keyset/order.rb)

and [`Gitlab::Pagination::Keyset::ColumnOrderDefinition`](https://gitlab.com/gitlab-org/gitlab/-/blob/master/lib/gitlab/pagination/keyset/column_order_definition.rb)

classes give an overview of the possible options for configuring the `ORDER BY` clause. You can

also find a few code examples in the

[keyset pagination](keyset_pagination.md#complex-order-configuration) documentation.